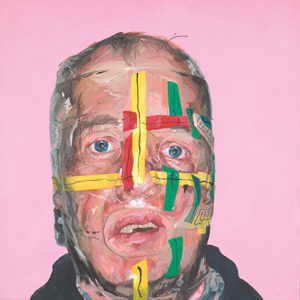

Bill Nelsen has led an interesting life. He has traveled all over the world, surveying land in far-off places — from Greenland to Ethiopia, Saudi Arabia to Mexico — for the U.S. Department of Defense. Bill, who is a Burnett Society member, worked for 41 years in what was previously known as the Army Map Service. The AMS produced military topographic maps for the armed forces, so Bill spent time trekking through remote areas, often walking at night so he could watch the stars to create map points on the ground.

It’s not necessarily what he imagined when he graduated from the University of Nebraska at Omaha with a degree in mathematics in 1962.

“My parents always wanted me to go to school,” Bill said. “They knew I’d be better off going to school and getting a degree. Fortunately, I was. My degree opened up a lot of doors.”

Bill returned to the U.S. in the late 1960s and settled down with an office position in Washington, D.C. Soon after, he met the woman who would become his wife at a Christmas party in the city.

“I got her phone number and gave her a call,” Bill said. “We dated the whole year of 1969, and we married in January 1970.”

Leoni Peperis Nelsen, who grew up in Tarpon Springs, Florida, in a tight-knit Greek community, worked at the U.S. State Department in diplomatic security until she retired. Public service was an integral part of the Nelsens’ married lives. So it made sense when Bill decided to make a planned gift to the University of Nebraska. In fact, Bill had been giving to the university since 1972.

“I had to thank them, thank the school, because if I didn’t have the degree, I wouldn’t have the job with the Army Map Service,” Bill said. “I was just giving money as an appreciation, giving a thank you to them for allowing me to get that degree, which really helped me.”

Bill’s planned gift, which he has directed to the University of Nebraska Medical Center, is also a gift of thanks — but not for his degree or his career. It’s a gift of thanks to his wife.

Leoni passed away just a few days before Christmas in 2019, and Bill’s grief for her still feels raw.

“It was a very quiet Christmas,” he said, “a very sad time for me.”

Leoni suffered from dementia and died from complications of the disease. Bill cared for Leoni while she endured it, and he helped care for his two sisters-in-law, who also have dementia. His gift to UNMC supports research into dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, along with macular degeneration, which he suffers from.

“I thought to myself, maybe we can find a cure for some of these diseases,” he said. “It won’t help Leoni, my wife, but it will help other people in society.”

Bill established a charitable gift annuity to make his donation. A charitable gift annuity provides a dependable income stream for the donor, who can allocate the remainder to support an area of the university that is personally meaningful to them.

For Bill, even after a lifetime of travel and interesting adventures, what was most meaningful was the memory of his wife — and helping others in her name.

“I wanted to do something,” he said. “I figure my wife is worth it.”