“They were just doing normal things,” she said. “They were cogs in the machine of this ideological hatred that he had.”

That day changed Ligon. It made her want to find the next McVeigh, the terrorists lurking among us — and stop them.

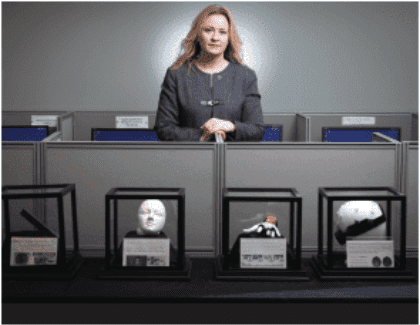

Today she is doing exactly that. Ligon is the head of NCITE — the National Counterterrorism, Innovation, Technology and Education Center, a U.S. Department of Homeland Security Center of Excellence. NCITE is dedicated to understanding, tracking and stopping domestic terrorists. It is a one-of-a-kind institution based at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, and it just earned UNO the largest grant in its history: $36.5 million awarded by DHS.

The grant lasts 10 years, but Ligon is already planning beyond that.

“This is an opportunity to build something that Nebraska can be known for,” she said.

On a recent Zoom call, NCITE students scroll through charts and graphs, tweaking variables and inputting data to make the lines bend and curve.

A little blue dot pops up on a map, corresponding with phone data and pinged locations.

It’s mesmerizing, and the students are excited about the software behind it. But they also understand the gravity of what they’re looking at.

That little blue dot is a potential terrorist.

“I’ve never been exposed to data in that way before,” said Liz Bender, a UNO junior majoring in criminology and criminal justice. “You read about it, but I never really thought I could have access to some of that data.”

Data is what drives NCITE. It began with the Jack & Stephanie Koraleski Commerce and Applied Behavioral Laboratory (CAB Lab).

Ligon pitched the idea to the former dean of the College of Business Administration, Louis Pol, Ph.D., in 2013. The proposal: high-tech tools capable of analyzing people’s emotions by tracking facial expressions, eye movement, brain activity and other neurophysiological responses. Her team would then apply that data to a broad range of subjects and answer questions like: What kind of business leaders are most effective, and how do terrorists recruit new members?

Terrorism and business may seem unusual bedfellows, but Pol said the CAB Lab’s business perspective was key to winning over DHS.

“From the very get-go,” Pol said, “when [Ligon] was applying those business perspectives to this study of violent extremist groups, they said, ‘Holy cow, this is different. We need to pay attention to this, and we need to pay attention to this person.’”

Along with its unique perspective, the program stood out because of its multidisciplinary nature — the College of Information Science and Technology is a key partner — and how much support it received from the university and community.

Ligon and her team pitched what would eventually become NCITE as part of a universitywide search for the next Big Ideas that would help UNO grow academically. The proposal led to increased funding at the university level and five new positions to support NCITE’s future growth.

Omaha philanthropists Jack and Stephanie Koraleski provided funding to launch the CAB Lab as well as a professorship, which Ligon holds. And a whole community stepped up to support the college’s new $17 million privately funded addition to Mammel Hall, which will house NCITE headquarters.

For students at NCITE, getting to solve real problems for DHS and helping stop terrorism are transformative opportunities. Bender says she learns something new every day and loves being encouraged to seek out her own projects.

“It’s not something I’ve experienced before,” she said. “It’s like the world is your oyster — do with it what you will.”

Bender said her interest in criminology stems from growing up in the era of school shootings.

“I wanted to understand why,” she said.

Tackling questions such as those is what makes NCITE a powerful experience for students, whom Ligon wants to mold into the nation’s best counterterrorism professionals ready to work in government, nonprofits or business.

“NCITE has given greater purpose to all of these students,” Ligon said, “so they can work together to solve something bigger than themselves.”

Something bigger — like stopping the next McVeigh before he, or she, has a chance to act.

The timing could not be more apt. As the U.S. struggles to recover from a global pandemic, a massive economic crisis and a highly divisive presidential election, risk factors for homegrown terrorism are extremely high.

“We have this boiling cauldron of risk factors that none of us really know what it’s going to lead to,” Ligon said. “There’s no more important time to have a DHS Center of Excellence than right now.”