New ‘Flight and Hope’ Exhibition on Display at Samuel Bak Museum

Students Learn the Art of Moving Forward Through the Work of Holocaust Survivor Samuel Bak

By Robyn Murray

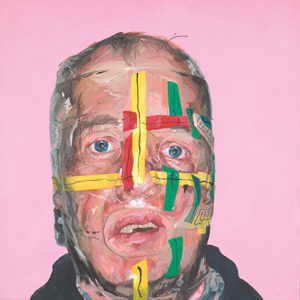

The boy stands with his hands in the air, despair and fear in his eyes. His body, scarred and pitted in stone, seems to emerge from a gravestone riddled with bullet holes. He holds a sling shot in his hand, a doomed defense against crushing force.

The painting, Icon of Loss, For the Many Davids, by Samuel Bak, captures and transforms an iconic image from the Holocaust of a young boy with his hands up, being marched to his death or another wartime horror. The original image, which became known as “Warsaw boy,” was captured by a Nazi photographer trying to document his efficiency as an executioner.

As Bak writes in his memoir, Painted in Words, the boy could have been him: “the same cap, same outgrown

coat, same short pants.”

Bak, a Lithuanian-American artist, was born in 1933 in Vilna, Poland, a city whose population of 60,000 Jews was annihilated during the Holocaust. By some accounts, as few as 2,700 Jews survived. Among them were Bak and his mother, who spent much of World War II hidden in a convent, aided by a Catholic nun. By age 11, Bak had lost his entire extended family, including his father, who was murdered days before Vilna’s liberation.

“The Holocaust was a laboratory of human behavior,” Bak said in a recent interview. “It taught us to see that in each one of us was the best and the worst.”

As a child, Bak was already a prolific painter. His first exhibit, at age nine, was organized by two poets he befriended while living in the Vilna Ghetto. Today, his work is featured in galleries around the world, and his vast collection — he reportedly can be working on 120 paintings simultaneously — is considered a seminal representation of the Holocaust and Jewish experience.

Bak’s work is particularly valuable as a teaching tool. His use of symbolism provides the viewer with a means to absorb difficult subject matter.

“They are windows into an alternate reality,” Bak said. “And in that reality, what they see are remains of a world that once existed and remains that have tried to reconstruct, somehow.”

Mark Celinscak, executive director of the Sam & Frances Fried Holocaust & Genocide Academy at UNO, has long recognized the value of Bak’s work in education.

“The art of Samuel Bak helps teachers and students make important connections between history and the moral choices they confront in their own lives,” Celinscak said.

Celinscak had incorporated Bak’s work into his curricula for years when he began a quest to bring the artist and his work to Omaha. In 2019, Witness: The Art of Samuel Bak drew approximately 4,500 visitors, including more than 2,000 middle and high school students, over its three-month run.

Moved by the response to his exhibit, Bak gifted a massive collection of his work — 512 pieces that span several decades — to UNO. And in February, Samuel Bak Museum: The Learning Center opened with a curated exhibit of his work and a series of events that welcomed 600 students, faculty and community members.

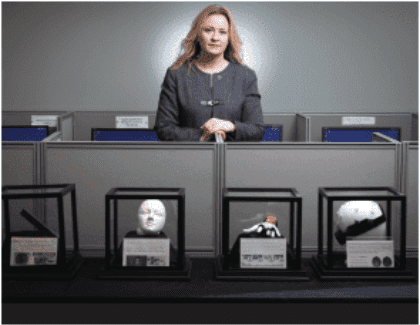

The museum is currently housed in a temporary space in Aksarben Village, but the goal is to find a permanent home for Bak’s collection on campus. It’s an ambition that will require private investment. The move is being led by a veteran of development, public administration and museum leadership, Hillary Nather-Detisch, who was hired as executive director in July 2022.

“The vision is a space where we talk about social justice, human rights, the Holocaust and genocide,” Nather-Detisch said. “It’s a conversation starter.” Nather-Detisch said the museum will bring people together to tackle hard questions about the nature of humanity, our shared history and our present. She envisions it as a versatile tool for educators that inspires hope despite the darkness of its subject matter.

“Sam’s work is an expression, yes, of his experience in the Holocaust, but it’s really about moving forward and how, for him, it’s a process,” said Nather-Detisch. “That’s how he’s processing everything that he experienced. It’s about hope … it’s about how do we move forward?”

That is one question Samuel Bak Museum: The Learning Center will encourage students and community members to wrestle with.

“My aspiration is to make people wonder and question all the assumptions that they have,” Bak said, “and try to understand the world in which we live.”

At 89, Bak continues to paint prolifically, charged with a sense of urgency to tell his story. He once said he wishes he could paint “one million of these Warsaw boys, for the number of children who were murdered.”

But the dozens Bak has painted live on, forever with their hands raised, for all those lost — broken but still present, haunting but hopeful in their resilience. As long as Bak’s paintings survive, so do they, each child given new life through the eyes of those who see them and remember their story.

Samuel Bak Museum: The Learning Center is free to the public. All ages are welcome. Visit bak.unomaha.edu for more information and upcoming events. Or visit the museum in person at 2289 S. 67th St., Omaha, Nebraska.

‘Flight and Hope’ Exhibition on Display at Samuel Bak Museum

A new exhibition of Samuel Bak’s artwork, “Flight and Hope,” is on display now through Dec. 22 at the University of Nebraska at Omaha’s Samuel Bak Museum: The Learning Center.

The exhibition explores themes of flight, journey and migration through Bak’s artwork. Informed by his experiences as a forced migrant and refugee in the aftermath of World War II, Bak’s work offers a potent reminder of the humanity of migrants, their flight from oppression and the fraught journey they undertake in the hope for a better life.

“Flight and Hope” is part of a broader conversation about the status of refugees in 2023, given the rising number of forced migrants around the globe. Nebraska has become home to thousands of resettled refugees since the late 1970s, following conflicts in Vietnam, Bosnia, Iraq, Afghanistan, Sudan and Syria. Refugees have built new homes, communities and businesses in Nebraska, creating a global heartland.

Numerous events, including a lecture series, poetry workshops and roundtables, are scheduled as part of the exhibition. For a full schedule, visit the museum’s website. All events are free and open to the public. The museum is located at 2289 67th St. in Aksarben Village near UNO’s Scott Campus.