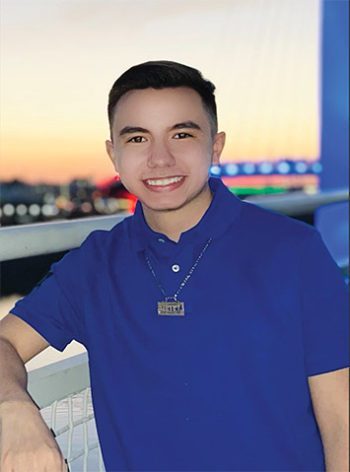

Marisa Macy, Ph.D., was recruited to UNK from the University of Central Florida after a 25-year career in early childhood education and special education.

After Traveling the Country, Early Childhood Specialist Comes to UNK for Her Dream Job

By Robyn Murray

Marisa Macy bubbles with excitement when she talks about living in Kearney.

“We love it here so much,” Macy said. “We have a 10-year-old daughter; she’s in fifth grade here in town, and Kearney is so perfect for us. UNK is so perfect for us. We just love it here.”

Macy, who grew up in Seattle, Washington, and has lived all over the country, accepted her job at the University of Nebraska at Kearney last fall — sight unseen. She interviewed during a surge in the COVID-19 pandemic, so the process was conducted virtually. She knew nearly nothing about Nebraska, but the job was so perfect, she jumped at the opportunity.

“When I learned about this position, I was so excited,” she said. “Everything about it on paper looked amazing to me, and I just was so excited. I told my husband I really want to apply for this job. It’s not just a job. It’s my dream job.”

The position is twofold: Macy is the Cille and Ron Williams Endowed Chair of Early Childhood Education at UNK as well as the Community Chair in Early Childhood Education at the Buffett Early Childhood Institute. The chair at UNK was established through a gift from University of Nebraska alumnus Ron Williams of Denver and his wife, Cille, in 2014.

The outreach embedded in the role is what excited Macy.

“This position is mainly focused on being a servant leader, where you’re providing leadership in the community and serving the needs of the people in our community,” she said.

Macy comes to the role from a 25-year career that began in special education. After four years teaching in a middle school in Buckley, Washington, Macy began working with families of special needs kids. Later she went into academia — researching and teaching on the subject as she traveled to follow her husband’s career, from Oregon to Pennsylvania, Texas to Florida. She earned her doctorate in special education from the University of Oregon and is considered not only a perfect fit for the role at UNK but an exemplary recruit.

Throughout her career, Macy has been motivated by a passion that she’d nurtured for as long as she can remember. And she has a photo to prove it: 3-year-old Marisa with her dolls, all lined up and facing her like students in a classroom. When she wasn’t playing teacher, Macy was watching “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” and wishing she could be like the gentle, cardigan-clad man who helped kids learn.

“I’m just so grateful for ‘Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood,’ because that’s how I learned how to speak English,” said Macy, whose mother spoke only Italian at home. “He spoke really slow; I could understand him. He was always so kind.”

Macy spent the first year in her new position traveling across Nebraska, learning about the early childhood education needs in the state’s communities and making connections. She’s already formed several that are likely to pay dividends. One is a collaboration with the University of Nebraska Medical Center’s Munroe-Meyer Institute to develop strategies to help prevent burnout among early childhood educators. Another is with the Nebraska Academy for Early Childhood Research at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, where she’s researching ways to ensure the quality of early childhood programs.

“I’ve never been anywhere that has had [collaboration] like this,” she said.

"It’s a very special place for our family"

Macy’s arrival in the state comes at a pivotal time. Not only is the University of Nebraska System finding innovative solutions to address the urgent statewide teacher shortage, but UNK is celebrating the three-year anniversary of the transformative Lavonne Kopecky Plambeck Early Childhood Education Center, a $7.8 million building that has already become a model as one of the best early childhood education centers in the nation.

The morning after Macy arrived, she realized she and her family are living right next door to it.

“I thought, oh, my gosh, this is so meant to be,” she said. “We get to see that every day.”

And she does. Macy picks up her daughter after school, and they hang out with the toddlers and kids who visit the Plambeck Center, while her husband, Robert Macy, finishes up his day in his new position as director of the Center for Entrepreneurship and Rural Development at the College of Business and Technology. Everything feels just right, like she’s finally where she’s meant to be.

“It’s a very special place for our family, for so many reasons, here at UNK,” Macy said.