The surgery wasn’t the hardest part.

The worst was squeezing his face into a tightly fitted plastic mask and lying down on a cold, metal table. Every day, he endured the same waves of claustrophobia as he kept his body still while the nurses secured him to the table and the sickening stench of his burning skin washed over him.

“I saw the experience turn a gentle, lovely man into someone who was being violent,” said Mark Gilbert, Ph.D., an artist and medical humanities professor at the University of Nebraska at Omaha.

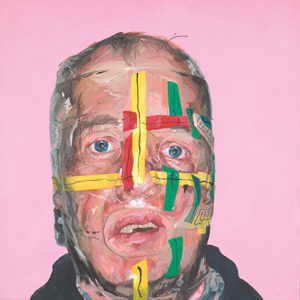

Gilbert met the man, Roland S., when he was undergoing radiation treatment for cancer of the upper jaw. Gilbert painted Roland’s portrait during the process — sitting with him during his surgery and radiation treatments and spending hours with him in his studio.

“It takes courage at the best of times to have somebody looking at you while they’re drawing you,” Gilbert said. “I took confidence in the fact that he had confidence in me. He trusted me to do justice to this part of his story.”

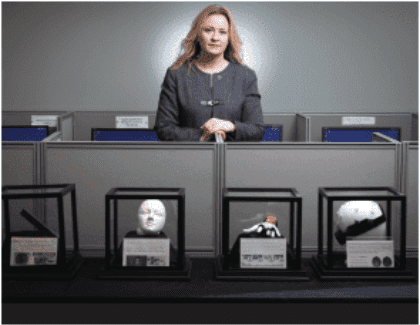

Roland’s portrait was part of “Saving Faces,” a project conceived by a surgeon at the Royal London Hospital, who commissioned Gilbert to paint portraits of patients undergoing facial reconstructive surgeries. The hope was the process of being painted would help them heal and adjust to their facial deformities.

While not a new idea, it has gained significant traction in recent years: the power of art and humanities to heal.

“Humanities aren’t just a pleasant distraction,” said Gilbert, who has conducted numerous studies on the impact of art on well-being. “They can allow us to engage with what we’ve found most challenging in a way that can be healing.”

“Saving Faces” was exhibited at UNO in 2006 through a partnership with the University of Nebraska Medical Center. That led to a 15-year relationship that resulted in Gilbert’s joint appointment as professor of studio art and medical humanities in 2020. Gilbert’s position is part of UNO’s medical humanities program, an interdisciplinary partnership that was established as a major in 2019.

The program is directed by Steve Langan, a poet and writing teacher with a background in public health administration. Langan came to the position after his experience as founder of the Seven Doctors Project, which paired doctors with writers and aimed to provide a creative outlet for physicians to

relieve stress and burnout. Langan said the impact was profound.

“Humanities and the arts are, in my experience, life-altering,” Langan said, “and that’s not an exaggeration.”

UNO’s medical humanities major has grown to include 80 students, who hail from various backgrounds and have a range of career goals.

It includes a long list of participating professors from UNO and UNMC in fields as varied as sociology and anthropology, philosophy, English, communication and social work. It is highly collaborative and involves organizations across the country, including New York City’s Theater for

Social Change.

“It’s been well known for a long time that various types of art — written art, literature, poetry, graphic arts, music — have had a dramatic effect on how people heal, particularly for serious and chronic diseases,” said Jeffrey P. Gold, M.D., chancellor

of UNMC.

As the program grows, Langan says it will not only focus on helping patients heal through engagement with the arts, but it will also aim to improve wellness among health care workers. Langan says the program is currently focused on tackling burnout, a problem exacerbated by the pandemic.

“We recognize the sky-high burnout numbers, sky-high suicide numbers. Physicians are at the top of that terrible list,” Langan said. “We believe that what we bring to the table helps alleviate the stress, suffering, the pain of not thinking about and talking about what ails us. We’re not trained therapists. But our specialties contain that inoculation.”

For Roland S., the process of sitting with Gilbert through one of the most challenging periods of his life and seeing the portrait of his face — the scars, the fear in his eyes — helped him turn his pain into something he could confront, and even into something beautiful.

“He turned something that was deeply upsetting into something that was powerful,” Gilbert said.

In August 2022, Gilbert’s work will be exhibited at the UNO Art Gallery alongside drawings by his late father, Norman Gilbert. For more information, contact Gilbert at 402-554-2420 or [email protected]