By Susan Houston Klaus

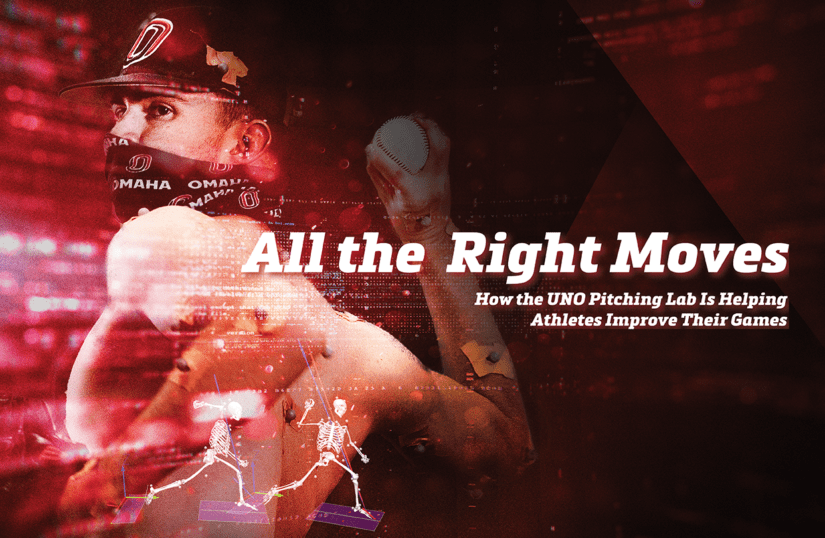

How the UNO Pitching Lab Is Helping Athletes Improve Their Games

The digital images generated in the University of Nebraska at Omaha Department of Biomechanics might prompt a double take. Human skeletons appear to be pitching a baseball or softball, spiking a volleyball or swinging a golf club. But these bundles of bones are actually living, breathing athletes — from UNO, the local community, the region and the country.

They’ve come to the UNO Pitching Lab in the Biomechanics Research Building for movement assessments designed to improve their performance and prevent injuries from taking them out of the game. It’s the first time the department has combined biomechanics, athletic training and data gathering to benefit the athletic community. And like other unique programs happening in the Biomechanics Research Building, it’s giving students experiences they wouldn’t find anywhere else.

The Biomechanics Research Building garners envy around the world for both its people and its equipment, said Jeff Kaipust, UNO’s assistant director for biomechanics. Opened in 2013 and expanded in 2019, the building represents the generosity of Nebraskans, particularly the Ruth and Bill Scott family, who provided the lead donations for the building’s construction and expansion, and the support of the UNO administration and University of Nebraska System.

“None of the wonderful things we do in UNO Biomechanics would have been possible without private support, especially from the Ruth and Bill Scott family,” said Nick Stergiou, Ph.D., assistant dean and director of the UNO Division of Biomechanics and Research Development.

“This support is fundamental for construction of our facilities,” Stergiou said. “It is also essential for retaining and attracting talented young scientists who work in the pitching lab.”

Together, those elements have created a place that puts a high value on collaboration — a place where, Kaipust said, “one lab doesn’t belong to one researcher; every space in our facility is shared.”

The lab is populated by people from around the world with all kinds of expertise, including in mathematics, engineering and kinesiology.

“From the brain to the individual muscles to the different properties of the ligaments, tendons and bones, we’re just trying to solve interesting problems on the way we move,” he said.

The idea for the pitching lab started with an athlete.

Tyler Hamer is a former NCAA Division I pitcher who played at the University of Illinois before transferring to UNO for his last two seasons. As he was completing his master’s degree in biomechanics at UNO in 2019, he mulled over his next move.

“As a player growing up, a pitcher in high school and also in college, baseball’s been a lot of who I was and who I still am now,” he said.

He wondered if it was possible to pursue a doctorate with his dissertation focused on baseball pitching. Hamer talked it over with his faculty adviser, Brian Knarr, Ph.D., an associate professor in the UNO Department of Biomechanics. For a decade, Knarr has been doing his own research on understanding how people move, how injuries can be prevented and how to optimize rehabilitation from an injury. He’s also a lifelong baseball fan.

With Knarr’s support, Hamer outlined an idea for a lab focused on the unique needs of athletes. He tested the system out on himself, again stepping on the mound to deliver pitch after pitch — this time, in the name of scientific research. Soon, the lab had the interest of others on campus.

That included Adam Rosen, Ph.D., and Sam Wilkins, Ph.D., at the UNO School of Health and Kinesiology. Both have been Division I baseball athletic trainers; now they train the trainers who work with UNO athletes and bring a clinical aspect to the lab. Hamer and the team also got buy-in — and an old pitching mound they reengineered to use in the lab — from UNO baseball coach Evan Porter.

The pitching lab officially hosted its first subjects in October 2019, bringing in UNO Baseball pitchers. They’ve returned regularly to check their progress. Porter said players have tweaked their movements and improved their velocity on the mound. But there’s also the unmeasurable part of the assessment he’s glad they have access to. Catching movements that may lead to injuries is crucial to preventing them and staying in the game. Having that information gives them added confidence as athletes, Porter said.

“It provides them with more knowledge about how their bodies work, how their mechanics work, and that leads to better tendencies, better performances and more wins, hopefully, for the Mavericks for the long term,” Porter said.

The collaboration among biomechanics, athletic training and the athletes they serve has been valuable for biomechanics as a program and for its students, said Knarr.

“It’s something that is incredibly attractive for students coming into the program,” Knarr said. “We’ve seen increases in recruiting and increases from the student body to come to our program to work with our athletes, to work with our faculty doing the science.”

Students also get a tremendous opportunity to work with athletes at an elite level, he said.

“Not many places in the country and across the world really have the opportunity to work with high-level athletes,” Knarr said. “Often, they’re either on professional teams or they’re siloed off in their academic or athletic programs. But some of the best opportunities to learn and to understand the sport are to work with athletes that are great at that sport.”

Baseball assessments were just the beginning for the lab.

In the past couple of years, the lab has expanded to include testing for UNO athletes in softball, volleyball, golf, swimming and diving, and men’s soccer, as well as players of middle-school age and up from the greater community. The lab has developed a reputation not only as an assessment destination, but also a learning resource for local students. Athletes with their eyes on the Major League Baseball draft have also made the trip from around the country to get advice on how to improve their performance and throwing velocity.

Marriah Buss recently visited the lab with her UNO Volleyball teammates for an assessment. An outside hitter, she’s been a standout on the court for years: In high school, she finished her years at Lincoln Lutheran with the second-most kills in Nebraska history. So, a particular finding from her assessment was more than a little surprising.

“One thing we learned about me is I have really bad shoulder mobility,” she said. “So, we’re wondering how I’m able to hit the ball, and how I’m able to hit it hard. Through the biomechanics testing, we learned it’s not through my shoulder that I’m hitting the ball, but it’s because of my hips, how they rotate and the speed at which they rotate.”

Buss said she was “just really shocked” by the information.

“Now I know that by working out my hips, it will improve my arm swing and how well I’m hitting the ball,” she said. “It’ll definitely become something I’m way more focused on now than I was before.”

Buss is looking forward to putting the newfound knowledge to work so she’s even more powerful when the season begins again in late August.

For Hamer, research in the lab has provided a bigger view of where his career may lead. In October 2021, he joined biomechanists from UNO Pitching Lab collaborator Wake Forest University in the Dominican Republic at the MLB International Combine in Santo Domingo. There, he operated the biomechanics pitching lab, collecting data for MLB teams to review for the draft season. His paper, co-authored with Rosen, was published in the Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine in March 2021.

Those experiences wouldn’t have been possible without those who originally put UNO Biomechanics on the map, Hamer said. “It’s really just the hard work that happened before I ever arrived here that’s allowed me and others working in the lab to make it what it is today,” he said. Hamer said, ever since he started playing baseball, he’s wanted to make it to the majors. Today, his work in the lab has helped him achieve that dream — just not in the way he imagined.

What’s next for him?

“It’s just kind of seeing where life takes me and just going each day as best as I can,” he said. “I’ve always been a believer in hard work, and if you work as hard as you want to, you can make anything happen.”